The Tree in our yard is old, some decades thick, trunk torqued. For many years, it was meticulously maintained, but then it was not. Still, it lives, lives intensely! I have pruned it hard, and still when a plant nerd comes over, they take one look and say, “You want to prune that this winter?!” The Tree changes everything about our yard: when it is green, the yard is green. When it is bare, it is winter.

From my perspective, trees don’t contain the actual spirits of humans (my mysticism runs in other directions). But still, I think of the tree as some kind of embodiment of Lillian Yuri Kodani, the woman who owned our house before she died. She spent 60-some years here. Long before us, she would have known the tree. As she lived her final years on the first floor of the house, this being would have dominated her view out the back window, as it does ours. She would have known that it held its leaves longer than the rest of the trees, and that it was slow to bud in the spring, and the feeling of it, looking up from the trunk.

We used to live down the block, so we knew Yuri (as she was known around here) a little bit, but this tree has forged a different kind of connection. We—Yuri and our family—are the people who have known this organism more intimately than anybody else on earth. I guess maybe the tree doesn’t embody her, so much as all of us, the tenders?

I invented many stories about the tree. Perhaps it was there when Yuri and her husband Eugene Kodani moved into the house in the mid-20th century. But how could I know the age of a living tree? At first, I tried to get a rough sense of things. I had looked at the tree thousands of times from all angles, but trees have a way of inviting your eyes to the whole, not the parts. The tree had become almost two-dimensional to me, a happy old thing with a lollipop head. The branch system, though, revealed a different topology. There is a hollow, a concavity on the west side. It grew up against a garage that’s no longer there, but that ghost remains in the limbs.

Still: no age.

The internet informed me that I could measure the circumference of the tree (37 inches), then divide by pi (3.14etc), and that (almost 12) would be the rough age of the tree. But, no. That’s ridiculous. This is an old tree, that bears the mysterious marks of time, like an ancient sperm whale.

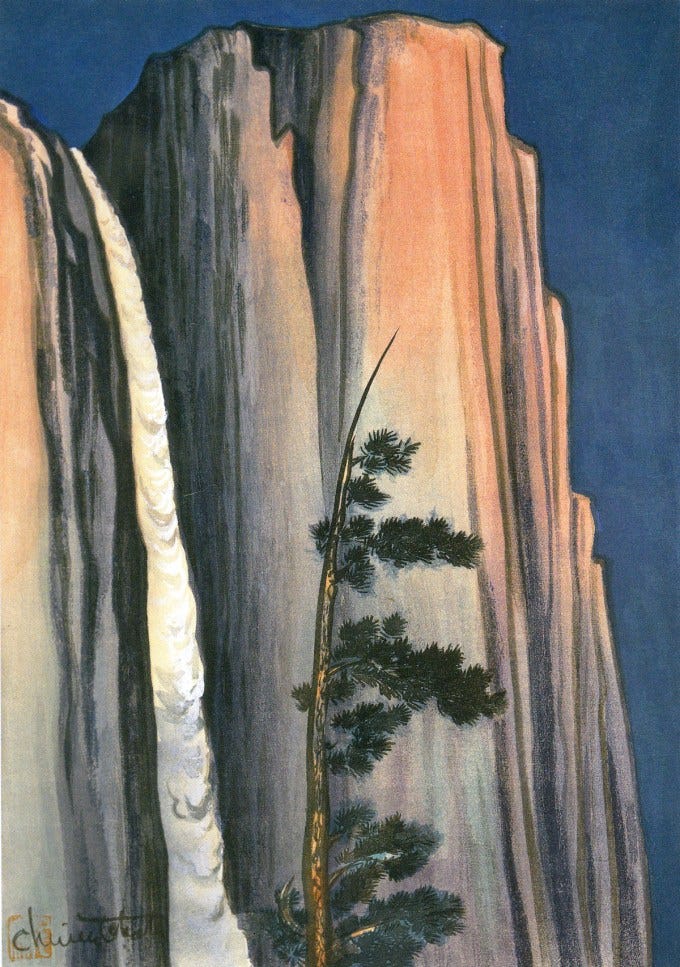

So, I asked Yuri’s daughters about the tree. Kimi and her sister Mia are two of the family history keepers. There is a lot of history to hold. Yuri’s father was Chiura Obata, a remarkable Japanese landscape painter, who came to the U.S. in the early 20th century. Obata made some of the most beautiful paintings ever of California, especially his work in the Sierra. Here’s my favorite, “Evening Glow at Yosemite Falls,” held at the Whitney Museum.

Obata taught art at UC Berkeley. His wife, Haruko, was an expert in ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement. They ran an art supply store on Telegraph Ave. But then came Executive Order 9066, and the great shame of the internment of Japanese Americans along the west coast.

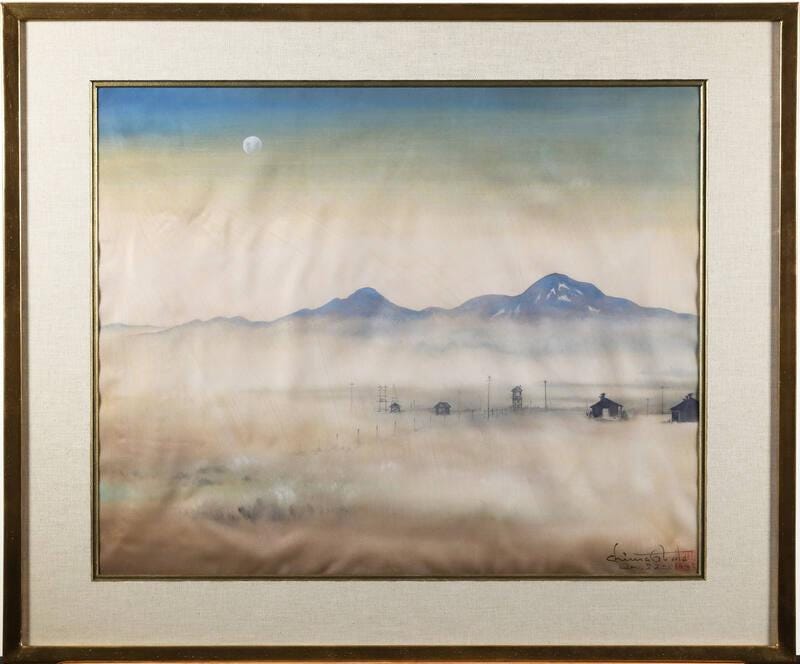

The Obata family (including a 15-year-old Yuri) were imprisoned, first at Tanforan and then at Topaz, in Utah.1 In both places, Chiura established art schools that trained hundreds of students, and helped “maintain one spot of normalcy.” Obata’s stark paintings from the Topaz period are as chilling as any artifact created by the imprisoned Japanese Americans. This one, “Moonlight Over Topaz,” is in the FDR Presidential Library and Museum collection.2

When the war ended, Obata was reinstated as a professor at Cal, and eventually the family’s life stabilized. Their son Gyo, who had fled to St. Louis, went on to co-found the huge architectural firm HO(bata)K. Yuri married Eugene Kodani, also an architect. Kodani had been interned, too, but in Arizona, then he served in the U.S. military in Italy. When he returned, he headed to Cal and got his architecture degree. The two of them settled into this very house in Oakland in 1957. They raised their kids much as we have raised our own: in a pack, neighbor kids running from house to house, screen doors banging open and shut. Their kids grew up. Eugene retired in the 90s. He died the year we moved to the block, 2011.

Yuri stayed in the house, watching the street repopulate with children, watching the apple tree bud and leaf and blossom and fruit. Yellowing leaves, last fruit, bare branches. New growth. Year after year.

And then in December of 2018, at age 91, she died peacefully in her sleep, a few feet from where I’m writing, a few feet more from the tree that we share.

In Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses, she tells of a visit with filmmaker Sam Green to visit some eucalyptus trees that had been planted by Mary Ellen Pleasant, a San Franciscan by choice, who had been born into slavery in 1812. They stood at the base of the eucalyptus, looking at curls of bark and leaves. “The trees made the past seem within reach in a way nothing else could: here were living things that had been planted and tended by a living being who was gone, but the trees that had been alive in her lifetime were in ours and might be after we were gone,” Solnit writes. “They changed the shape of time.”

Where, then, in these remarkable Obata-Kodani lives, did this apple tree enter the picture window?

Kimi conferred with Mia and they returned a best guess: their father had planted the tree, probably in the 1980s. The apple had been preceded by a bing cherry, and an apricot that’s now long gone. Their grandparents, the Obatas, also had Santa Rosa plums in their nearby yard. “Our dad liked the annual rituals of pruning and harvesting the fruit trees,” Kimi told me. She sent me this photo she took of her parents with a friend of Mia’s in the yard. It’s 1977. You can see the old cherry. You can see Yuri laughing. You can see the clothes line she always used.

“My mom used to make apricot fruit leather from all the extra ripe fruit, roll them up on plastic wrap, and store them in the freezer. Later in the summer we would take the rolls (orange for apricot and purple for the tangy plum) on our Sierra backpack trips,” Kimi said. “When the old fruit trees died, dad must have decided to plant the apple tree.”

This tree, all this to say, might be more of my contemporary than I had guessed, something like 40 years old. A peer, as much as a mentor. Mid-life, amid life, you can see it here on the December day we met in 2019. Much has changed, but the clothesline remains.

The truth is: from a horticultural perspective, the apple tree in our backyard is nothing special. The apples are reddish yellow, not too sweet, not too tart, not too tasty. But to be a part of this tree’s life is to be a part of the story of those who planted it. To keep this tree alive is to tend some small piece of Eugene’s memory, some mote of Yuri, some component of the tragedy of what happened to their families, to feel into the concave space where this tree never got to grow, and yet still thrives, and where its branches are searching out the new light, even right this minute.

I want to hear your stories of trees, or rather, of The Tree in your life at some point. The one you shepherded through some part of its life, or that comforted you through a hard time. You glimpsed The Tree from a bay window. It was out in the courtyard. It grew into your sidewalk. Your grandfather painted it over and over, but you never could understand why. The Tree sat in a large pot at the bottom of the stairs. It was your guidestar on a favorite run. It was the last thing alive in the yard. It was a giant oak that you ran beneath as you time-lapsed from child to young adult, and then you (or it) disappeared.

Tell me these stories. Leave a comment. Or send me photos or drawings (alexis.madrigal@gmail.com). I want us all to share our trees. And I will, if y’all send me them.

You can hear then 102-year-old Yae Wada describe this experience on Forum a couple years ago.

How did it come into the possession of FDR’s library? The museum explains: “In May 1943, shortly after Eleanor Roosevelt’s well publicized visit to the Gila River camp in Arizona, a delegation from the Japanese American Citizens League visited the White House to express their gratitude for her concern for the treatment of Japanese Americans. During their visit they presented this painting of the Topaz camp to the First Lady. On June 16, Mrs. Roosevelt sent a letter to Obata thanking him for the painting. She displayed it in her New York City apartment until her death.”

When I was born on Long Island in the 1960s, my dad planted a tree in our front yard. We moved when I was 7 and again when I was 12 because of my dad’s jobs and I was pretty tortured by us leaving that tree and those moves. It was literally the only thing left to remind me of my time as young kid, and it was a distant memory. I remember so clearly the night before our second move, super pissed at my dad, facing another uprooting, that I would NEVER move my kids and subject them to the pain he was putting me through.

Advance 20 years. My first child is born and I have an image of me, crazed by sleep deprivation, planting a royal star magnolia at our first house for my March-born daughter just days after she was born. Two years later, a kousa dogwood for my April-born son. Five years after that - a coral bark maple for my January born son. All promising to blossom around their birthdays.

So, I half lied to my 12 year old self twice. We did move from our first house, but just a mile away. And damn if I didn’t didn’t dig up two of the trees and bring them with us (the magnolia being too big at that point, replaced by a new one). We moved 10 years after that, 1/4 mile from the first house and I uprooted all three trees by hand and moved them…the last one as the moving truck was filling house #3 with the stuff from house #2.

My kids take three trees for granted now. I don’t.

We moved into this house in 1985. I chose it because it had appeared to me in a dream, so I never even looked in the back yard. When I did, I discovered a huge avocado tree. I name things and somewhere along the line, that tree became Ambrose. I have no idea why. Things, like my characters, name themselves and tell me who they are. I fought this for years believing I was abnormal since I wasn't trained as a writer and survived my first fifty years as a dissociative with twelve selves. Even now at 72, my therapist will tell me, "That's normal, Fran, for everyone," because I still don't understand how most people work. Then I read an interview with Alice Walker who talked about how her characters would arrive and take over, and in another interview, I watched Toni Morrison explain that she never meant to write about slavery, but the characters showed up and refused to leave so the world now has Beloved. Seeing them, and James Baldwin, as spiritual mentors, I stopped fighting and began enjoying the appearance of characters like ghosts that speak from the hundreds of rooms in my mind.

Ambrose has rarely been pruned. Long ago, a man who came to replace my garage door stopped and stared up at Ambrose in awe. He said, "I grew up on an avocado farm, and that is the biggest avocado tree I've ever seen!" He's the one who told me Ambrose only bore one avocado, if any because, back in the day, you needed a male and female avocado tree near each other for pollination. There's only one other avocado tree in the neighborhood, April, who bears the most delicious Haas avocados I've ever eaten. She's even bigger than Ambrose but the garage door guy didn't see her. Ambrose's lone avocados, bitten once and dropped by squirrels, is a smooth-skinned variety with watery fruit compared to a Haas. I have no idea what kind it is, but he and April are apparently not compatible.

A year after we moved here, my ex embarked on an affair, and my 12-year marriage was suddenly over. Ambrose became more than a wonderful, shady companion. He held me up over and over as I sobbed with my arms around his rough trunk or laid my hand against him for comfort. He's survived years of California drought during which he still grows beautiful, soft red leaves in the Spring that slowly change into dark green fans that wave in the hot Santa Ana winds when the desert is cooler than the city. He also grows clusters of tiny flowers that are rarely pollinated because there is no companion tree. I talk to Ambrose every day, sometimes thanking him for his steadfast modeling of survival that has kept me from leaving Earth too early. He's shown me how to send my depression deep into the Earth like his roots and raise my face to the sun, like his leaves. I'm still here because he's still here.

I worry, now, that I'll have to move into some insipid thing called "Senior Living," and leave Ambrose behind. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power discovered him and recently pruned him away from the precious phone lines for only the fourth time since I've known him. They did a terrible job because they cared for the lines, not him, but I don't worry because he always grows back, faster for the pruning.

If I have a choice, and no one can say that I don't, I want my spirit to pass into Ambrose when I die. I'll add my strength to his and together we'll withstand anything climate change throws at us as we spread shade over new generations of Angelenos.