Read this one with the smell of tomato leaves on your hands

An introduction to the new newsletter, what plants do to us, the endless and the infinite

Hello. Been a while! The dough has been rising, what can I say? BUT I return to you with a new vision for this newsletter.

You probably subscribed some time ago, perhaps when it was called Five Intriguing Things (2012ish), Real Future (2015ish), or 5IT (2017+). Well, I’ve rechristened the newsletter again: Oakland Garden Club. More on why in a minute. In any case, thank you for sticking with me.

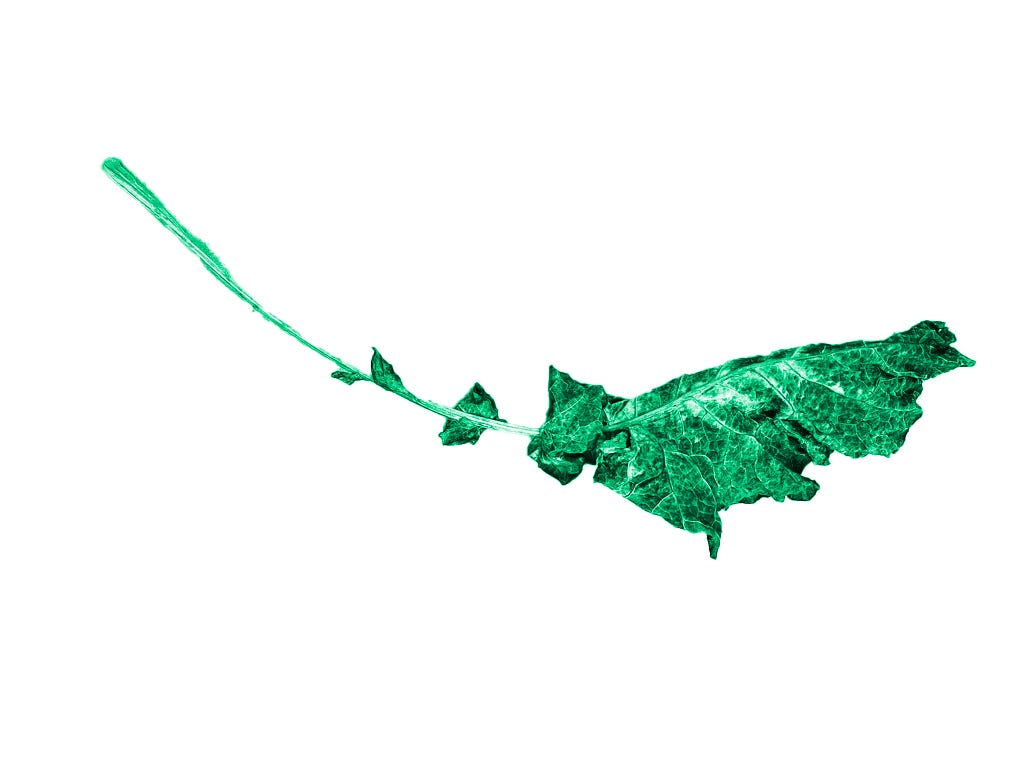

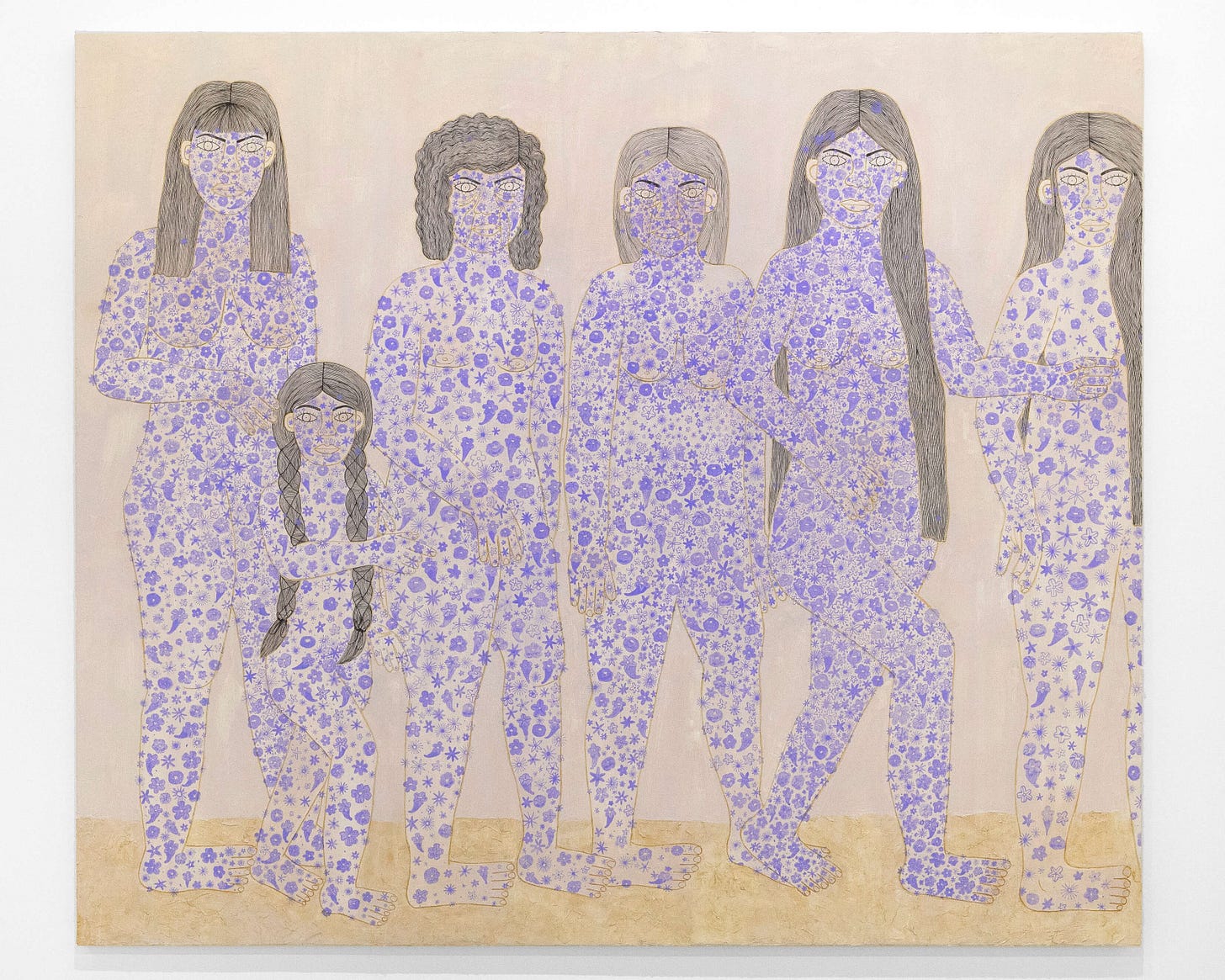

If you are new here, perhaps you would like to subscribe. Do you think about plants? Are you curious about what changes in you when you consider the more-than-human world? Plants as plants and plants as portals to ecology, history, global cultural exchange. I’m inspired by: Ross Gay, Jenny Odell, MFK Fisher (but for plants), the history of Mary Kuhn, the art of Kija Lucas, the Florentine Codex research of Diana Magaloni Kerpel, the streetwear of Gangsters Buy Flowers. That’s what we’re doing here. And it’s free.

For now, here’s what I’d like to get across: how good do tomato leaves smell when you’re pruning them, or even just brush by them on your way down a path? Tomato leaves do not smell like tomatoes taste. No, the smell is the omen of a future tomato, the promise of the sweet fruit.

Two years ago—the first in our new house—I had an amazing set of plants. We have three big pots, so they were called Uno, Dos, y Tres. Uno probably produced a thousand sungolds, each one ripening in its time and slot, like the notes in a scale. Always, they ripen like this, the ones closest to the core first, the outer reaches last.

I love being overwhelmed by a productive tomato plant. At first, each ripe tomato is special and quickly gobbled up, maybe a day or two early (sorry!). But as summer goes on, you just can’t keep up. Every day, you wobble outside to eat your fill and still there are more. Caprese. Sauce. Salsas. Still more. You beg people to come take them and they can’t believe you would give away such treasure. Point being: We can be made generous by the sheer glory of even a single tomato plant.

So, last year, my expectations were riding high. I planted early and tried not to hover too much. For whatever reason, Uno, Dos, y Tres produced, but nothing like the year before.

Something else happened, tho. In maybe May, I noticed that the ground around the pots had begun to sprout little tomato seedlings. I carefully dug a couple out and stuck them in pots. But when I came back a few days later, there were more, and then more, and then more. I learned to pull them up intact, barely the length of a pinkie, the tender taproot no bigger than a tooth pick and so much more delicate. I’ve never been as gentle as I became tending these babies. I gave away a couple dozen to friends and neighbors, and by all accounts that returned to my ears, these plants overwhelmed their caretakers with tomatoes, and it was good.

I watched those seedlings go out the gate happily, but I also felt a tinge of envy when I’d receive a grown-up photo of one of my plantitas, given my plants’ meager production. Then, I was doing some weeding, when I noticed that I’d missed a seedling nestled in a clump of grass. I cleaned up the grass and left it in place, happy to have one of Uno’s kids still kicking around the house.

Over the next few months, that little guy grew up SO BIG that it launched itself up and over the tomato cages of Tres, then Dos, then Uno. And it, too, produced a wild number of sweet tomatoes until long after the marigolds had bloomed, all the way until the leaves fell off the apple tree.

The Endless and The Infinite

I came up as a technology writer during the rise of “social media,” but I don’t like writing about the internet much anymore. I used to be able to map what happened online to things in the rest of life. As the platforms grew, those mappings began to warp. A realm developed called extremely online, driven by the evolutionary processes of attention. A company would create an opportunity to be seen, and then people would fill the niche to the point of exploitation. The systems fed on themselves, breeding and inbreeding too many times. Next thing you know, you got QAnon people believing some message board guy is the key to the world, while everyone else speedruns every genre of America’s Funniest Home video and sitcom trope. It’s mostly bad now.

And endless. Like, the platforms will not let you get to the end of it, scroll as you might. There’s a whole genre of YouTube videos about walking to the end of the Minecraft world space. Apparently, it would take over 800 hours of walking a video game character through pixels. Absurd! But you could watch YouTube videos about it for the rest of your life. Even more absurd! This is a metaphor for all internet right now.

The platforms reorganize themselves before you cybernetically. You're coming to like what the algorithm is showing you, while the algorithm is showing you things it thinks you will like. This tends to suck people in and down, rather than expanding their cones of interest or circles of concern. All platforms simply must care too much about what you want. A platform will never ignore you like a tree will. In the extremely online world, you have too much control, but not enough freedom.

What about outside, the thing we persist in calling The Real World? That’s different. Whole books can tell you that: Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights or Jenny Odell’s Saving Time or Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek or David Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous.

I don’t mean “nature” or “wilderness” (nor their baggage). I don’t mean a magical redwood grove (tho damn they are magical). I just mean any old place. This place, say.

This place.

Or, sure, this place.

These places are not endless. If you like one flowering plum in front of a logistics depot, you cannot simply will another one to show up on the next block, or tell the tree to flower in July, or forego the decade it took for the tree to grow into its specific shape in that specific spot, given the sunlight and water and nutrients and time that it has had available. (Which, if you’ve ever planted a tree, can be frustrating.)

You know what the real world is, though? Infinite. Any place in the world has so many dimensions to explore—animal, plant, mineral, bacterial, fungal, historical, cultural, anthropological, temporal. But understanding what is there requires knowledge and time and a quite different kind of attention.

For me, the best entry point to the real world has been plants. On the internet, attention is the monetizable part of your consciousness. To train your mind on plants requires a fuller, broader, deeper, longer kind of attention. This is growing attention. It crosses oceans and slips inside the openings to flowers. The earth’s orbit around the sun really starts to mean something.

Raising plants is an act of care. Understanding local ecosystems brings depth to the idea of home. Sharing seeds and cuttings builds community.

Plants are beautiful. Plants are beautiful. Animals like ourselves have an irreducible attraction to their patterns and smells that reaches back beyond the first human.

Deepening our relationship with plants is not only about how to care for their physical needs (though it’s nice to reach that level of understanding). Plants span the botanical and the cultural. Plants offer routes into (difficult and beautiful) transnational histories. Plants, with their radically different sense of time, can help us unstick from the gridded, quantified time that has ruled our days since we began to burn ancient plants to speed production. Plants are the underlying basis of life on earth, beings attuned precisely to the sun’s rays and our earth’s subterranean potentials. Some plants will outlive us by 50 generations. Others germinate, live, and die in the span of time it takes to read one fat book.

So, Oakland Garden Club?

This newsletter is going to be my development space for projects. One exciting thing: KQED Forum, the radio show I co-host, is about to get a new digital community space. I am ecstatic! And I’ll send out invites to that spot in the next few weeks. Different from this plant-y world, but we all need some civic cultivation, too.

For this newsletter, the primary purpose is to bring a new thing into existence: Oakland Garden Club, a publisher of streetwear and tiny books about the encounters that writers and artists have with individual plants. (You can help!)

Each season will feature drops of books and interrelated clothes. Books and streetwear may seem like unlike things, and they are, I guess. But streetwear spreads and grows. You might call it viral, but I would prefer to think of it as growing like a weed (a good thing). We want to spread plant-mindedness. It feels like an antidote to a deep ache, something near the liver. Tiny books can go far, but t-shirts can go farther.

What if, though, a t-shirt can also be an idea? There are a lot of streetwear brands that traffic in plant *vibes*. Like, a shirt that just says P L A N T S on it. OK, fine. Others cut-and-paste random nature-y stuff onto fabric. Also, fine.

But what if a shirt or a pair of joggers could be a whole argument, a full explanation, a portal to real understanding of nasturtiums or the dark reactions of photosynthesis or tule reeds or indigo or book 11 of the Florentine Codex? That would be awesome. And maybe more people would come closer to the shirt and maybe to the books and ultimately to the plants and what they have to teach us.

This newsletter will share my own new plant writing and point to others who are doing the kind of work that we’ll publish, from Liz Hernandez’s jacaranda ghost women (see below) to Michael Pollan’s tulips from The Botany of Desire to Andre Parise and Gabriel Toledo’s work on the electrical signals of the bean plant in The Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal Intelligence to Eleanor Perenyi’s acidic wisdom about 20th-century gardening.

So, I understand if you came for the technology stuff and you’re out now for this season of the newsletter. Totally get it. But if you want to come along on this new adventure, I’d be delighted. Oakland Garden Club is for everyone, whether you can grow one succulent in a pot in your sharehouse or you have a vast native pollinator garden somewhere in the hills. You can even hate gardening. What we love is plants as plants and plants as portals. Welcome.

Your description of the smell of tomato plants is so timely and spot-on. Every day I take a mid-morning break from working at home to tend to the tomato plants. They’re in an elevated planting bed a tad too close to the hot tub on one side and a fig tree that’s exploding in growth on the other, so I have to squeeze myself into a narrow gap to get to the center plants.

The cool, leafy greenness of the plants is face-high, so I get a deep and rich dose of tomato plant air with every inhalation. The zen of gardening, away from my laptop even just for a few minutes, is restorative and grounding.

Thank you for putting such a beautiful voice to this simple and necessary pleasure.

Evolution is good. I’m not surprised that you’ve pulled away from writing about the internet. It’s changed, as you’ve said, to something less about being an explorer in a strange new world with seemingly limitless possibilities, to something more sinister, like hard drugs. What’s that people say about hard drugs, I don’t want to try them because I’m afraid that I’ll like it? (And then get pulled down beneath the waves)

I’d never grown anything from seed before in my 47 years until 6 months ago, when I planted some tomatillos from seed. Tomatillos aren’t common in Australia where I live, so when I saw the seeds at the local hardware store, I knew I had to try. I miss them from when I used to live in Denver, like missing something you can’t have.

So I planted the seeds, probably 2 months too late, and yet they grew, despite my mismanagement and terrible staking, and in the end I was able to make one batch of salsa from the fruit, and it was a delight.

Good luck with your new seedling!