"only in gardening could I stop shrieking"

a satchel of miniature updates: Pajaro fundraiser, lichen, that new frond feeling, the bloom, a poem

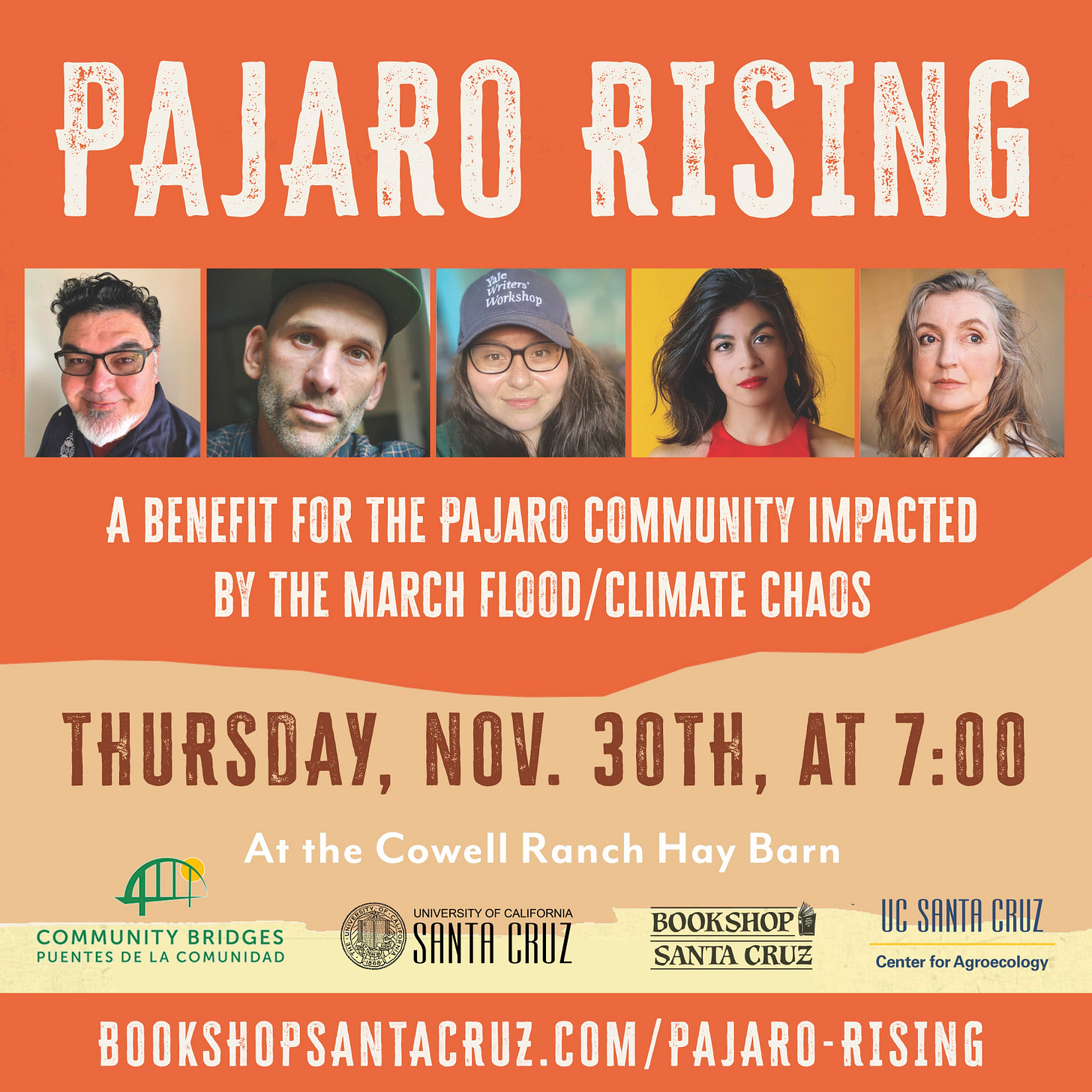

Last winter, the town of Pajaro was flooded by its namesake river. Pajaro, like many places farmworkers live, exists precariously, near a levee everyone knew would eventually fail. While the emergency disappeared from the news many months ago, the recovery is still far from over. Hence this amazing benefit in Santa Cruz with Jaime Cortez, Rebecca Solnit, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Claudia Ramirez Flores, and me. It’s this Thursday, the 30th! Go buy tickets (go big!) and help out the community. Then, come say hello.

I’m reading a fascinating tiny book about lichens, The Lichen Museum by A. Laurie Palmer. It begins in Santa Cruz, behind the Ross Dress for Less, on a levee enclosing the San Lorenzo River, about 20 minutes north of Pajaro. Looking through a magnifying glass, Palmer sees what the security guards and surreptitious smokers do not see back there. “It is still a surprise,” Palmer writes, “to meet pattern and system at such a miniature scale, when what looks like dirt, or paint, or a smear of something unspeakable reveals itself differently.”

But why, this these times (these times), should one pay attention to the lichens? “It seems paradoxical because lichens are so small, and the crises destroying the earth and shattering human relations now are so overwhelming, that such a practice could matter at all,” Palmer continues. “But attending to lichens is attending to relationships, to qualities of connection. It is about revaluing forms of life and being that are generally ignored if not literally stepped on, and learning from those beings how we might practice living differently.”

I’m writing something about ferns for Taxonomy Press’s Floral Observer. Y’all know I am a flower guy. I love the flower worlds. In Mesoamerica, many groups related flowers to the sun, to realm up here in the known. The moon and the minerals were part of a different divine geography, as reflected even in the choice of pigments for paintings in the Florentine Codex.1

Well, ferns—the largest group of non-flowering plants—seem to me to belong to both sun and moon, flower and earth, or maybe they’re at the border between them (near the lichens?). They are of the forest, and also what is under the forest.

But what captures me with ferns is that new frond feeling, bearing, as it does, such a close resemblance to the bud about to bloom feeling. Ferns, tho, remind me of my days staring at the Mandelbrot set in the After Dark screensaver (I can’t be the only one who remembers). Fractals and chaos, pattern and system. Repetition, but always something new.

As with all gardening, I am appreciator, not expert, so my process has been to stare, to marvel. An ancient spiral you can plant with your own hands or find in the wet, dark refuges of the world. I want to learn the complex biology that allows a fern fiddlehead to unfurl into frond. And I also just want to feel those words in my mouth, and to touch the bristles. Are they soft? Not quite. Caterpillar, nautilus, sleeping mammal. Yes, and not quite.

My marigolds are still in full bloom. Each year, it’s different, and I find myself searching back through old photos—“is this how it was?” I don’t know why I expect regularity. Each year is its own time. Still: many plants are trying to sleep and these guys are still just going.

In conclusion, a poem, from the anthology Leaning Toward Light: Poems for gardens & the hands that tend them, edited by Tess Taylor. This is C.D. Wright with a poem for these times (these times), “Song of the Gourd.”

In gardening I continued to sit on my side of the car: to

drive whenever possible at the usual level of distraction:

in gardening I shat nails glass contaminated dirt and

threw up on the new shoots: in gardening I learned to

praise things I had dreaded: I pushed the hair out of my

face: I felt less responsible for one man’s death one

woman’s long-term isolation: my bones softened: in

gardening I lost nickels and ring settings I uncovered

buttons and marbles: I lay half the worm aside and

sought the rest: I sought myself in the bucket and won-

dered why I came into being in the first place: in gar-

dening I turned away from the television and went

around smelling of offal and inedible parts of the

chicken: in gardening I said excelsior: in gardening I re-

quired no company I had to forgive my own failure to

perceive how things were: I went out barelegged at

dusk and dug and dug and dug: I hit rock my ovaries

softened: in gardening I was protean as in no other

realm before or since: I longed to torch my old belong-

ings and belch a little flame of satisfaction: in gardening

I longed to stroll farther into soundlessness: I could al-

most forget what happened many swift years ago in

Arkansas: I felt like a god from down under: chthonian:

in gardening I thought this is it body and soul I am

home at least: excelsior: praise the grass: in gardening I

fled the fold that supported the war: only in gardening

could I stop shrieking: stop: stop the slaughter: only in

gardening could I press my ear to the ground to hear

my soul let out an unyielding noise: my lines softened: I

turned the water onto the joy-filled boychild: only in

gardening did I feel fit to partake to go on trembling in

the last light: I confess the abject urge to weed your

beds while the bittersweet overwhelmed my daylilies: I

summoned the courage to grin: I climbed the hill with

my bucket and slept like a dipper in the cool of your

body: besotted with growth; shot through by green

Until next time.

You can watch this thrilling video of scholar Diana Magaloni-Kerpel describing her painstaking, brilliant work.

Thank you for sharing. You have given me starting points to launch deeper into the world of lichens and this poetry book.

I am so in love with your writing and newsletter! I keep forwarding it to my friends and hope they sign up. The poem was touching and I'm going to buy that lichen book.

Yes, I remember the Mandelbrot set, and have been obsessed with fractals, crop circles, the Serpentine Mound, and labyrinths for decades.

Do you know about Pando, the forest of quaking Aspen in Utah? 100 acres, an estimated 66,000 tons, between 85,000 and 1 million years old, and the largest living organism on Earth (that we know of so far.) Why living organism? Because the Pando forest turned out to be one tree. She's a clonal grove with every tree having the same DNA as the original mother tree. I find that freaking awesome!

Last thing (no, I don't have ADHD. I'm a polymath and my mind is like a fractal.) I want to give a shout-out to the Theodore Payne Foundation. I visited as part of an eco-tour and keep sending people there. I know you're based in Oakland, but if you or your readers get to visit SoCal, skip Disneyland (heretical, I know, but spend that large money on plants) and go to the Foundation: https://theodorepayne.org/