A feeling for the organism, wildflower edition

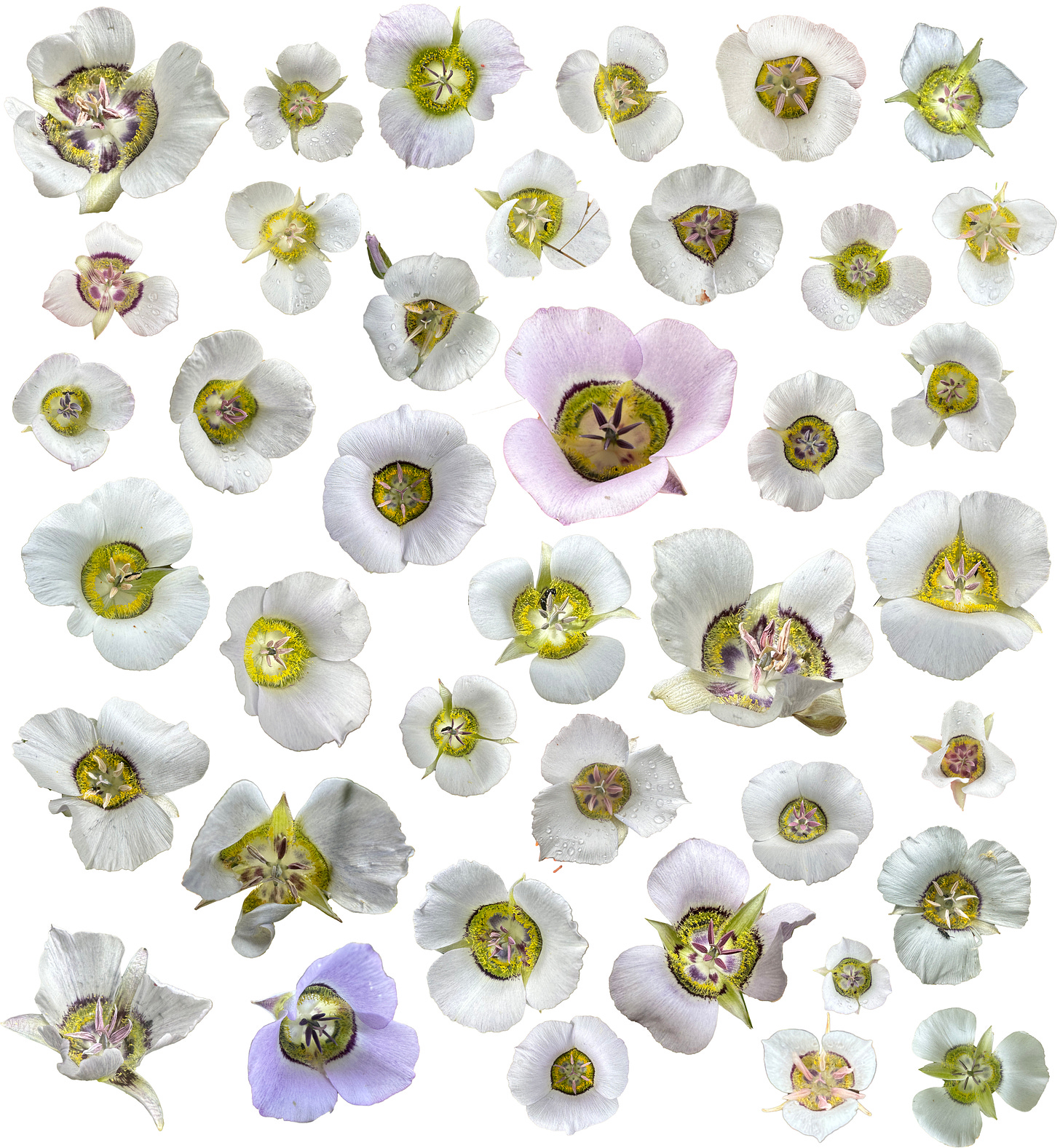

39 blooms of Calochortus gunnisonii, a field of mutant maize, and one fava bean

Each summer, we spend some time in the Rocky Mountains. This year, after the wet winter, the Colorado hills are blooming with all kinds of beautiful things—larkspur, penstemon, yarrow. Batches of aster. Even the sage feels freshly scrubbed and bright. But I’m always on the lookout for mariposa lilies. This genus arose seven million years ago in what is now California, and dozens of species are now spread throughout the west from BC to Guatemala. Around here, the local beauty is Calochortus gunnisonii, with a range from Wyoming through Colorado down into New Mexico.

Here’s your type specimen: three simple petals, six stamen surrounding the pistil’s Mercedes tip, a ring of dark purplish pigment, delicate yellow hairs. Perched on thin and unadorned stalks, they are like a grass that decided to be fabulous.

At every life stage, they are beautiful. I particularly like when the flowers begin to die. Their leaves separate. The sepals become more prominent. And the dark pigments inside the flower’s cup become more visible. Time goes on, and the petals roll into little scrolls as the pistil grows into what will become a torpedo of a seed pod.

There is no better wildflower genus, IMHO. And one thing that’s always fascinated me about these particular Colorado flowers is the variation they show in their inner petal pigmentation and overall color. Flower to flower, the differences are not insignificant, and don’t seem to be explained by any immediately observable environmental cue. Each one is simply a different organism with a particular way of embodying the species.

Perhaps I was primed to be thinking about the organismness of particular plants. I just finished reading the magisterial biography of Barbara McClintock, A Feeling for the Organism, by the MIT philosopher and historian of science, Evelyn Fox Keller. McClintock became famously acquainted with each mutant plant she grew in her corn field. By carefully examining the plants, their kernels, and their chromosomes all together, she eventually deduced wildly unexpected features of the genome … before even the discovery of DNA.

“It was her conviction that the closer her focus, the greater her attention to individual detail, to the unique characteristics of a single plant, of a single kernel, of a single chromosome,” Keller wrote, “the more she could learn about the general principles by which the maize plant as a whole was organized, the better her ‘feeling for the organism.’”

I have more coming on McClintock, but that’s really the deep end of the biology pool for me, and I’ve struggled to articulate why McClintock’s work is so fascinating.

This is part of it, though. So much of horticulture and gardening revolves around trying to grow the biggest, best things. It’s like the Westminster dog show: all these creatures trying to show how they precisely fit the archetype. But I like street dogs, living things that embody themselves and their own unpedigreed lineages.

And I love that McClintock wasn’t someone trying to create the perfect embodiment of corn, the Arnold Schwarzenegger of maize. No: she was using these plants to probe how they responded to stress, how their chromosomes functioned, and she appreciated what each one might tell her about the subcellular world that scientists were just beginning to probe and the plant itself.

So, wandering down a steep sage canyon with a mountain stream to my left, I set about documenting each mariposa lily that I came across, photographing each one as I flitted patch to patch. I got good photographs of 39 of them, which I set into a collage to highlight their variations. As I cut out each flower, I found surprise after surprise. A little spider eyeing another bug. Thunderstorm rain drops clinging to a petal. Rings of royal purple, and Laker purple, and dark reddish-purple. A pollinator hugging a stamen. A tiny red mite on a bright white flower. Perfect cups and the elegant wrinkled twist of an aging petal. Who needs a perfect bloom at the prime of its efflorescence?

The obvious-but-still-interesting thing: some of the plants have purplish petals. I have not found a specific scientific explanation for why this happens. To me, on an aesthetic level, it’s as if the colored ring simply cannot contain the pigment in some plants, and the purple leaks out. You’ll notice some of them have just a slight blush, while one is almost pink and another a true purple-purple. Some things just happen. You’ll only see the whole space of organismal potential if you look at a lot of individuals.

The creative studio Companion—Platform has created a project that I love precisely because it asks us to attend to an individual plant. It’s a seed packet designed for the service Are.na. Contents: a single fava bean.

In explaining the work, Calvin Rocchio described how they calibrated the amount of gardening advice to give people. “We tried to find just the right balance of imperative information on the back of the packet to provide a good place to begin,” he said, “but with emphasis on having a close, observational relationship with your plant by discovering its needs as an individual, rather than on a species level.”

Emphasis mine. Like: we don’t grow FAVA BEAN, we grow this plant. Rocchio’s creative partner, Lexi Visco, described the fava bean’s “tamagotchi energy” (lol). “Formally, the tamagotchi and the fava bean are both round and have a similar relationship with your palm,” she said. “They also foster a similar one-to-one relationship: You learn how to care for the being so it can flourish. Through daily attention, you will learn how to keep it happy and enable its growth.”

Except instead of annoying beeps and fake needs, your reward will be spiraling growth, beautiful flowers, and eventually … more seeds … Such is the “gift alchemy” of plantdom (see: Robin Wall Kimmerer).

I will probably never plant a Calochortus gunnisonii. But I know where they live, and my version of passing on the gift is to take people to see them, to point out the details that make their species special, and to notice when some individual plant is doing things differently. My whole map of this region southwest of Rocky Mountain National Park is really a map of where the mariposa lilies are. They are how I orient myself in this beautiful place near the line that divides the continent’s waters. It’s fine to talk about named peaks or hydrological significance, but have you seen the patch of lilies by the creek, near where the trail loses coherence?

Cuttings

Connie Zheng’s A Fog Bath and Seed Search in Three Parts is lovely: "As anyone who has propagated a branch or succulent leaf knows, many plants possess a similar talent for perpetuality. Perhaps it is the quietest, most un-spectacular beings that will outlast all else.”

Gardens of our Ancestors: King Nezahualcóyotl's Royal Gardens

In the realm of wild plants, the Welwitschia is a real contender for wildest: “In Afrikaans, the plant is named ‘tweeblaarkanniedood,’ which means ‘two leaves that cannot die.’ The naming is apt: Welwitschia grows only two leaves — and continuously — in a lifetime that can last millenniums.”

The Oakland History Center’s Instagram tipped me off to the remarkable tradition of the California Spring Garden Show (aka the Oakland Garden Show). I need to see more from 1942, where apparently the theme was “Floating Gardens of Xochimilco” (!).

A study of the home gardens created by African American, Mexican, and Chinese migrants to Chicago. Totally fascinating comparisons here, and the literature review in here is a good reminder about how little scholarship is produced about gardens.

I like Mariposa lilies too, for all the reasons you write about, many of which I didn't know until now. Thank you.

Up in the hills of Oakland in Redwood Regional Park there is a remarkable patch in the Serpentine hillside and a second alongside the Dunn trail on the ridge. I wait for them each year and am always delighted to see them.